The aftermath of the Piazza della Loggia bombing, a 1974 attack carried out by the Evola-inspired group Ordine Nuovo.

“If anyone deviates from the ‘rules’, that is to say sees the debate-form for the sham it is, or takes to the streets, displacing the imposed ‘platform’ for the construction of a new order, then the true face of all those who defend ‘debate’ is revealed: suddenly those who are most powerful pretend that they are under siege by those who are ‘unreasonable’…

Debate is a cover-story: never having to be honest about your true intentions while pretending to be open-minded. Debate dissociates argument from passion; phony talking-points from real life. There are multiple things we do not agree about – and we also disagree with the way in which you want us to say it. The narrowness of the debate-form allows those with power to dictate the boundaries of ‘reasonable’ discussion and ignore (or police) everything that happens outside it.” – Nina Power, 2015/16

“I’m very interested… in what it means to live as freely and honestly as possible…, to not be manipulated as much as possible, and to recognise when someone is trying to do this to you.” – Nina Power, 2019

A few words by way of introduction: this is a response to a small controversy that I’m just catching up with, but which took place a few months back, and so anyone who has any interest in the subject probably thinks of it as old news by now. Clearly, I’m not part of the overlapping London left/artworld/academic scenes most directly involved (it obviously takes a fair while for the stagecoach carrying the latest London drama and gossip to reach my local town crier!), and so it might be worth taking a moment to justify why I’m taking an interest at all, especially as it involves responding to some deeply personal stuff.

First off, there is a sense in which I was invited to participate in the conversation from the very first open letter, which was addressed “To all who oppose fascism”. The details of Nina Power’s specific situation aside, the spread of alt-right, or neoreactionary or whatever, ideas is something that concerns a lot of people, and so it seems not unreasonable to take an interest in it.

Secondly, even though I’m not particularly part of the same scenes, I am interested in Nina Power’s ideas and work: I read and enjoyed One-Dimensional Woman back in the day, it’s a book that I’ve bought a copy of to give as a present for someone I like and care about, I’ve definitely recommended that people I know read her work and so on. Perhaps that’s not the closest bond in the world, but that is some kind of investment, even if it’s closer to the passive star-fan kind of relationship than anything more meaningful and mutual.

Thirdly, because, as she reminds us, Power was caught up in the state repression that fell on participants in the 2010 student movement. I tend to take the view that we do owe a certain respect and consideration to those who’ve been up against, or close to, the sharp end, or even the blunt end, of the state’s attention, people like the Shrewsbury pickets, those who were out in 84-85, the blacklisted construction workers, those caught up by spycops (to touch on another example that can be tricky at times) and so on. Since the following is largely an explanation of why I think Power’s going badly, dangerously wrong, it might seem like a strange way of paying respect and consideration; but sometimes I think respecting people can look like taking the time to explain why you disagree with them as calmly and politely as possible, where it might be tempting to just say “lol get lost you wrongun” or similar.

And finally, the most important reason, which is that since first finding the story, and especially since reading Power’s side of it, it’s stuck in my head and bothered away at me, which I think is usually why people write things. Apologies if the above introduction seems a bit lengthy and rambling, but I think compared to what Power’s written it’s relatively short and concise.

Anyway, the core of the story, for anyone who’s not familiar with it, is that Power’s been accused of both transphobia and fascist/neoreactionary sympathies, and wrote up a two–part response. I’m not going to go into her views on gender too much here, although in passing I do find it notable how often the two seem to go hand-in-hand, for some reason you never seem to get people becoming less sympathetic to the far-right at the same time as getting into “gender critical”/trans-exclusionary versions of feminism.

The first part is, I think, much more interesting and compelling, but it doesn’t really have much to say about the main points of disagreement, so all I have to say in response is (and excuse the weird shift from third to second person here, but it’s hard to read such a personal piece of writing and not respond in kind):

If Nina Power does happen to read this, I want to acknowledge that the situations and experiences described in that piece are really horrible, and for whatever it can possibly be worth I really am sorry that you and those close to you had to go through them. I don’t know how much our big utopian dreams are worth in this day and age, but I think that wanting to work towards the end of the state, a world where no-one would have to go through that particular ordeal ever again, is a good goal to have. I hope that in the future you can continue making contributions to that sort of goal, perhaps alongside some of the people who are criticising you, and who you’re currently scorning as authoritarian, police-like, cancellers and so on.

The second part, “Cancelled”, begins with a lengthy critique of people who disagree with things, or who take their disagreements too seriously, or who impose consequences that might seem excessive as a result of those disagreements. This is, in the abstract, hard to disagree with outright: certainly, we can all think of instances where we, or people we care about, have been hurt as a result of a disagreement, and we can wish they hadn’t happened, or had happened differently. But it’s also hard to accept outright: are we supposed to never draw lines, never say something is unacceptable, that beyond a certain point we will not go? To use Power’s favoured term, deciding that under no circumstances can anything or anyone ever be “cancelled” is a recipe for paralysis, as meaningless as deciding that everything and everyone is cancelled.

At some point I think it’s necessary to say, for instance, that one is against Anders Breivik. And, at the risk of being overly controversial, of being exposed as an authoritarian canceller, I would extend that to saying that I am against anyone who is proud of inspiring Breivik’s attack.

Power does still apparently understand herself as being against fascism, and gives a broad definition of that term; but she skips over one of the most relevant questions here, which is whether fascism includes the thought of self-proclaimed “superfascist” Julius Evola. And if it does, what are the conclusions that follow on from that?

Where she does touch on specifics, Power’s favoured method is the broad sweeping conflation, “What the cancellers of today want to say is – we have decided that this person is ‘over’ – call them DC Miller, call them Sam Kriss, call them Deanna Havas, call them TERFs, call them Lucia Diego, call them Nina Power, call them Angela Nagle, call them Satan, call them fascists, call them Nazis, call them ‘problematic’, call them ‘cancelled’, try to stop them speaking, try to smear them politically and personally, use lies, use exaggeration, use anything you can think of to get rid of them. We are right because they are wrong, and they are wrong because they say something or behave in ways we do not.”

This is a cheap trick, and a fairly meaningless one. I could equally well say that “I am writing this to challenge the people who say that we should discuss the ideas of Evola and Nick Land, and that Death in June are good, and that the royal family are shapeshifting lizards who killed Princess Diana and that Robert Mueller and Trump are working together to fight Hillary Clinton’s deep state paedophile ring.” Note that I don’t have to prove that Power or anyone close to her has actually said any such thing, I can just say those things in the same sentence, and, if I have any particularly credulous readers who are inclined to take everything I say on trust, then there you go, I’ve “shown” that Power and those who agree with her have ludicrous views.

Beyond this, it might be worth taking a look at those names in slightly closer detail. Presumably this is a list of people who Power feels have been unfairly persecuted; but I’m not sure that stacking all those names together has quite the intended effect.

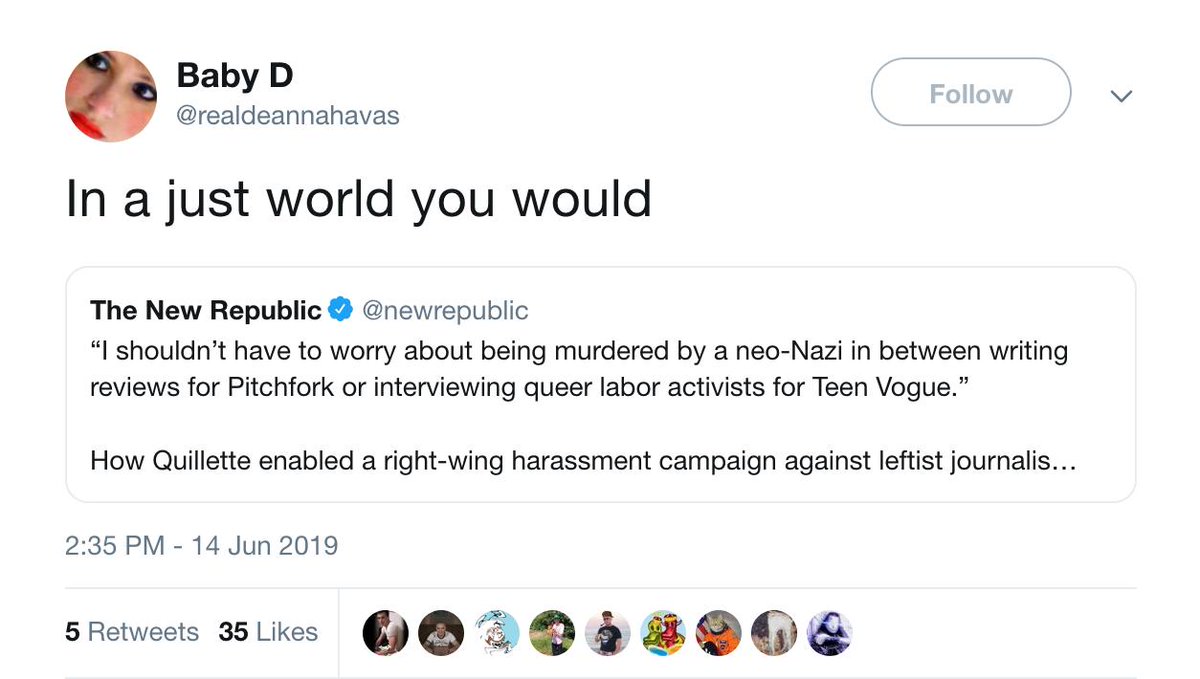

For instance, I didn’t recognise the name Deanna Havas at first, and had to look her up; it turns out that she’s the person who recently told an antifascist journalist complaining about getting death threats from nazis that those death threats were right and just.*

Perhaps this was intended as a joke, but if one wants to make unkind jokes about people who are currently dealing with death threats from nazis I, being the authoritarian police-like canceller I am, would suggest that maybe one could make such jokes quietly, to close friends, behind closed doors or maybe even in a park or on a hill, and perhaps consider not addressing those “jokes” directly to the people facing death threats? But of course, if I say that Havas is problematic or wrong for saying something that I disagree with, then I become one of Power’s authoritarian censoring cancellers; so how, precisely, do we deal with those telling our comrades that they should be be killed, that death threats against them are just?

Similarly, Angela Nagle feels like an odd name to shoehorn into this list. There’s a lot to be said about Nagle, and all the things that are wrong with her work; but one of the first things that stood out to me when I encountered her work is how little kindness or generosity there is in it. If the purpose of Power’s article is to plead for people to treat those who disagree with them more charitably and fairly, I don’t think there’s much to be learned from Nagle on the subject.

But this sweeping conflation is just a warm-up, Power manages to cram even more ingredients in for her next trick: “They used to know us. They want to pretend they now do not, lest they too get infected by this thing they call ‘fascism’. They want to suggest that anyone who deviates from the script – and what is the script this week – oh I don’t know – that LD50 was a ‘fascist recruitment ground’, that no-platforming people who have a second-wave feminist position on sex and gender is a good and righteous thing to do, that anyone who voted to leave the EU is a terrible person, that we shouldn’t discuss fascist ideas and iconography, that talking about nature leads directly somehow to someone shooting up a mosque, that it is good to say that everyone is a victim apart from ‘cis white men’, that people need to be protected from views that disagree with their own, that irony should be banned, that memes are dangerous, etc. etc.”

By the end of the sentence, Power appears to have forgotten how it started, and who can blame her? Again, here we have some obviously stupid ideas – apparently “they” want to say that anyone who voted to leave the EU is individually terrible, and that irony should be banned, why not throw in that they want to ban children from singing baa baa black sheep, and that they’re coming to bend your bananas or possibly straighten them – mixed in with some rather more defensible ones. Such as, for instance, the claim that a space that hosted a range of far-right, nationalist and anti-immigrant speakers, talking to admiring audiences with members who spoke of their support for David Duke, could be described as a fascist recruitment ground.

In another fragment, Power tells us that “they” say “that we shouldn’t discuss fascist ideas and iconography”. I don’t think that anyone actually says this. There are whole podcasts, and blogs like slackbastard and three-way fight, and books like Insurgent Supremacists and Ctrl-Alt-Delete and so on, that do very little other than discuss fascist ideas and iconography. As far as I’m aware, no-one, or at least no-one on the antifascist side, objects to them doing this, so I don’t think that’s where the disagreement actually lies. I suspect the real disagreement regards, for instance, whether people want to hear Death in June discuss fascism. Here, I will happily admit that I’m not interested in hearing what a group founded by National Front members, one that was still associating with militant Nazis from National Action decades later, have to say about fascism. Perhaps I’m being closed-minded here, and I could really benefit from listening to more of Douglas Pearce’s views, or Boyd Rice or Brett Stevens or whoever; but let’s not play coy and try to pretend that an objection to listening to fascists is actually an objection to talking about fascism.

In passing, the reference to “people who have a second-wave feminist position on sex and gender” is similarly slippery, as if it were meaningful to talk about “a second-wave feminist position” like that was a single coherent thing, as though there weren’t fierce disagreements between second-wave radical feminists and second-wave Marxist feminists, or indeed between second-wave radical feminists and other second-wave radical feminists, etc. I certainly haven’t noticed anyone trying to no-platform Silvia Federici lately.

The list peters out with “that memes are dangerous”, which again seems somewhat unarguable in the age of Brenton Tarrant’s “real life effort posting”. Are “remove kebab” and “subscribe to pewdiepie” just harmless japes now? Does “screw your optics” count as a meme yet? How about “bowl patrol”? I remember back in the day, Counterfire organised a “festival of dangerous ideas”, with Power being one of the most interesting-sounding speakers; but do ideas lose the ability to be dangerous if they’re written in impact font in a top text/bottom text format?

Next, Power suggests that the fundamental disagreement is about “the question of what can be discussed, and where, and by who. Can we all talk about anything everywhere?” This, at least, has a very simple answer: no, we can’t. Perhaps if we’re discussing normative ethical ideals, the world as we would like to see it, then that might be a nice dream; but if we’re talking about the world as it is, a world governed by the rule of private property, then we can usually say what the property owners allow, where they’ll allow it. For instance, Power’s writing, and this reply, are both hosted by wordpress, which means that we can talk about the things their terms of service allow; if we want to talk about anything at all in a coffee shop, we will usually be expected to buy a coffee first or else be asked to leave; we can’t get our views printed in the Sun or the Mail because that’s not how it works; anything we say anywhere in this country will be expected to comply with public order legislation, Prevent duties and so on.

In this world, those spaces that aren’t governed by the logic of capital are often carved out for some specific purpose. That being the case, I don’t really see a problem with, for instance, a group of students who’ve occupied a lecture hall to protest against an increase in student fees not wanting to let Nick Clegg use that space to talk about how increasing student fees are actually great; or an anarchist bookfair deciding that they want to just use that space to discuss anarchist ideas, rather than welcoming any weird reactionary with a cause to promote; or, in general, people running a specific space deciding that those with “a second-wave feminist position on sex and gender” can go get their ideas printed in the Guardian or New Statesman or Mail or Sun instead.

After this, Power moves on to a defence of Daniel Miller, noting that he made himself unpopular with his defence of LD50, but skipping over the questions of the threats he made against people who disagreed with him on the subject, and also his apparent fondness for Julius Evola. I would be interested to hear more about what exactly Daniel Miller thinks about Evola, and also what he thinks about his fellow Evola fans, like the various Evola-inspired Italian fascist terror groups, Steve Bannon, the Wolves of Vinland, much of the alt-right and so on.

Power complains that “I don’t even want to say that Daniel isn’t a ‘fascist’ because it’s not the point, I don’t want to play this game, because it’s your game, it’s a boring game. It reminds me of The Young Ones, where most everyone and everything is a ‘fascist’, although everyone seems to have forgotten that this was a comedy.”

But there is a difference between calling everyone and everything a fascist** and being suspicious of people who seem to have a very strong interest in the ideas of “super-fascist” theorists. Perhaps Miller will clarify this point, but I suspect not; it seems like his game is the “refusing to say how far I agree or disagree with fascists” game, and he seems to like that game a lot.

In passing, we can cast a similarly suspicious glance at Justin Murphy: perhaps “fascist” isn’t quite the right term for his vision of “neo-feudal techno-communism”, but I defy anyone to read his vision of a hierarchically stratified class society based around technologies of perfect control and not shudder at the totalitarianism:

“Basically it would have a producer elite, and this is where a lot of my left-wing friends start rolling their eyes, because it basically is kind of like an aristocracy… Imagine something like the Internet of Things — you know, all of these home devices that we see more and more nowadays that have sensors built in and can passively and easily monitor all types of measures in the environment. Imagine connecting that up to a blockchain, and specifically Smart Contracts, so that basically the patch is being constantly measured, your behavior in the patch is being constantly measured. You might have, say, skin conductance measures on your wrist; there might be audio speakers recording everyone’s voice at all times…

Well, all of the speech that people are speaking would be constantly compared to some database of truth. It could be Wikipedia or whatever. And every single statement would have some sort of probability of being true or false, or something like that. That could all be automated through the Internet of Things feeding this information the internet, and basically checking it for truth or falsity. And then you have some sort of model that says, if a statement has a probability of being false that is higher than — maybe set it really high to be careful, right? — 95 percent, so only lies that can be really strongly confirmed… Those are going to get reported to the community as a whole.

If you have X amount of bad behaviors, then you lose your entitlement from the aristocrat producers.”

Approaching the ending, Power tells us that “Daniel is an honourable, kind, brave and interesting man. A man who is against authoritarian behaviour of all kinds, including that on the left, which makes him very much not a ‘fascist’.” This feels like an interesting reversal of the usual question of separating the art and the artist: instead of asking whether and how we can or should enjoy work produced by a person who does bad things in their personal life, we’re told that someone is very nice in their personal life, and so we shouldn’t trouble ourselves about the fact that their work appears to be promoting the ideas of a fascist theorist.

The being “against authoritarian behaviour of all kinds, including that on the left” tells us very little as well, as there are plenty of fascists who are happy to proclaim that they’re against authoritarian behaviour on the left. Troy Southgate says that he’s a national anarchist; Augustus Sol Invictus has been a candidate for the Libertarian Party, and everyone knows that libertarianism is the opposite of authoritarianism, so he must not be a fascist either, nevermind his actual fasces tattoo. Richard Moult says that “I hold no political views save that of championing individual freedoms, as long as those freedoms do not seek to cause suffering to others – with these “others” also including all the non-human life forms we share this planet with”, but apparently this pro-freedom, anti-suffering stance is compatible with having spent years and years helping to run an occult nazi cult that promotes random acts of rape and murder. And so on.

As for the rest of Miller’s good qualities, I’m reminded of that passage quoted by Power in the first part of her statement:

“One can destroy one’s self or another with all the appearance of profound cosmic compassion. This compassion radiates out to everywhere except where the relevant people are.”

I don’t doubt that Miller is kind and compassionate to some people, perhaps even to many people. But this compassion didn’t appear to radiate out when he warned “Time is running out for these clueless little sociopaths… patience for these kinds of twisted people is ending. They themselves can feel this and sleep badly, haunted by bad dreams… Make them think you’re bluffing as you bait them into a killshot.” That does not seem like a particularly kind thing to say.

Likewise, I’m not sure that Miller’s compassion extends to those who would be harmed, or have already been harmed, by a revival of Evola-inspired terror attacks, or those who would suffer under the kinds of authoritarian regime that Evola or Justin Murphy dream of.

Perhaps Power and her new friends are very interesting debaters; but as a wise person once said, “There are multiple things we do not agree about – and we also disagree with the way in which you want us to say it.”

*admittedly, this particular charming exchange took place after Power’s article was written and posted, but I don’t think it’s the first time Havas has acted like an arsehole, so it doesn’t seem too out of character.

**although attentive readers may notice that this is pretty much the attitude taken by Foucault/D&G in that section she cites, so apparently saying that everything is fascist is good when Foucault says it, but not otherwise?

the death threats weren’t the plausible sort. K.Kelly was showing off how fabulous (teen vogue) and edgy (death threats!) her metropolitan elite existence is. d.havas response was measured and funny. yr massive over sensitive over explaining account of it all is too laboured. Kelly used to write and like all kinds of dodgy metal before she got woke and clutched pearls. she should be ashamed. and in a just world would get way more plausible death threats.

Thank you for that sensible and reasoned response, person who is definitely not a dodgy twat of any kind. Have you ever considered fucking off?

DC Miller’s thoughts on Evola are accessible – why not bother to check them out before writing this?

Accessible where? Are they in written form anywhere? Would you be able to provide a summary? I have read as much as I can stand of his pompous burblings about LD50, but he stays off the topic of Evola in those.

Pingback: Edgelords with thin skins: on the difficulty of free speech absolutism and “the right to discuss ideas” | Cautiously pessimistic

Pingback: SWERF and TERF: The Red-Brown Alliance in Policing Gender – Transnational Solidarity Network

Pingback: The end of the affair: some reflections on 2019 | Cautiously pessimistic

Pingback: Swastikas for Numpty: Catching up with the vexing antics of an unfunny double-act | Cautiously pessimistic

Pingback: Platforms – Nina Power | Full Stop